Has your teacher been telling you to study constantly and you feel you can’t escape the study cycle? Well here are some easy tips to get you on track with your studying!!

Firstly I recommend creating a study timetable to allocate time effectively for each subject. In this timetable it is also essential to include time for yourself. This may include going to the gym, or planning when you might read your favourite book or play sport for your local team. It is important to plan your days as it gives you a sense of organisation and structure to your studying schedule. It is also essential to not allocate huge amounts of time which you may not be able to stay focused on for that long. Ensuring to designate your time effectively is essential for proactive studying.

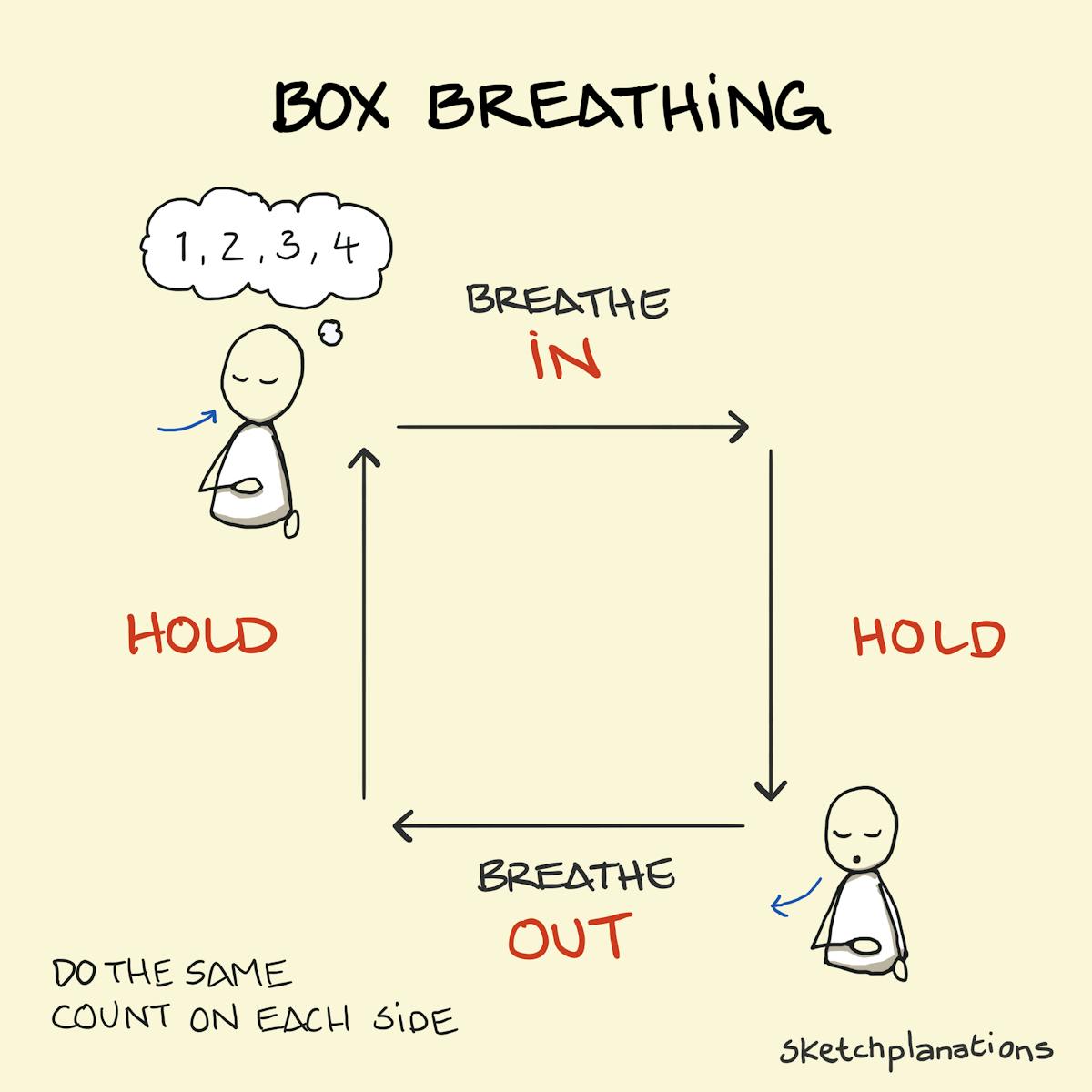

Secondly, continuing to take regular breaks is essential in allowing your brain to recover and process the information. A break may include going to the bathroom or eating some food to relax and allow your brain to absorb everything you just learnt. Avoid using your phone for prolonged periods of time during these breaks as it can throw your schedule off and lead you to endless doomscrolling which is the worst case scenario.

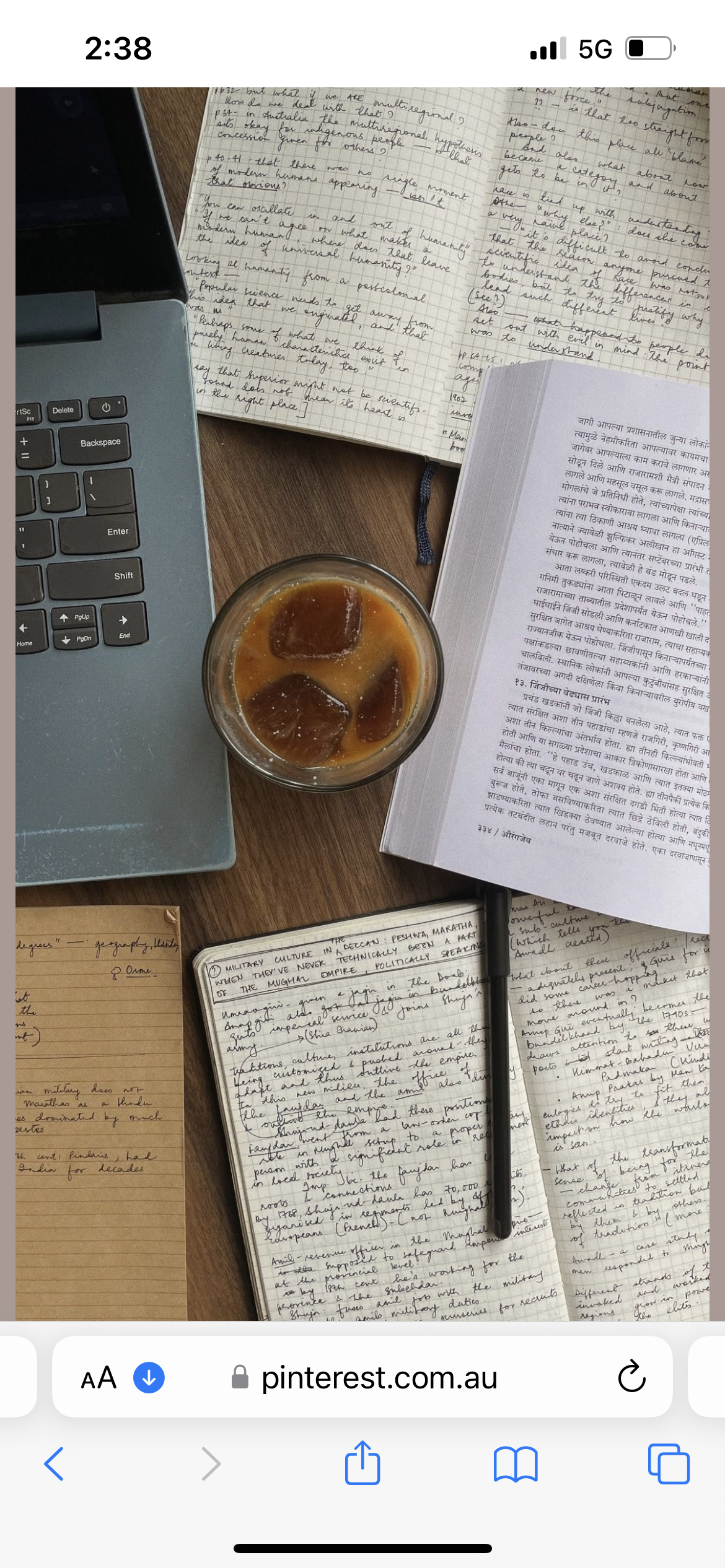

Thirdly it is essential to study in ways which you are most familiar with. There is no point adopting study techniques which don’t match your learning style as it will lead you to become less interested in learning. Techniques may include using bright colours and specific stationary to creatively present your work. Or alternatively wearing noise cancelling headphones may eliminate distractions and allow for you to focus on the work at hand. We are all different so our techniques will vary, but it is important to find the best way which works for you.

In conclusion, using study techniques which work best for you are extremely important in laying down foundations and seeking success in the future in all academic endeavors!!

Happy studying!!

Flora Carabitsios