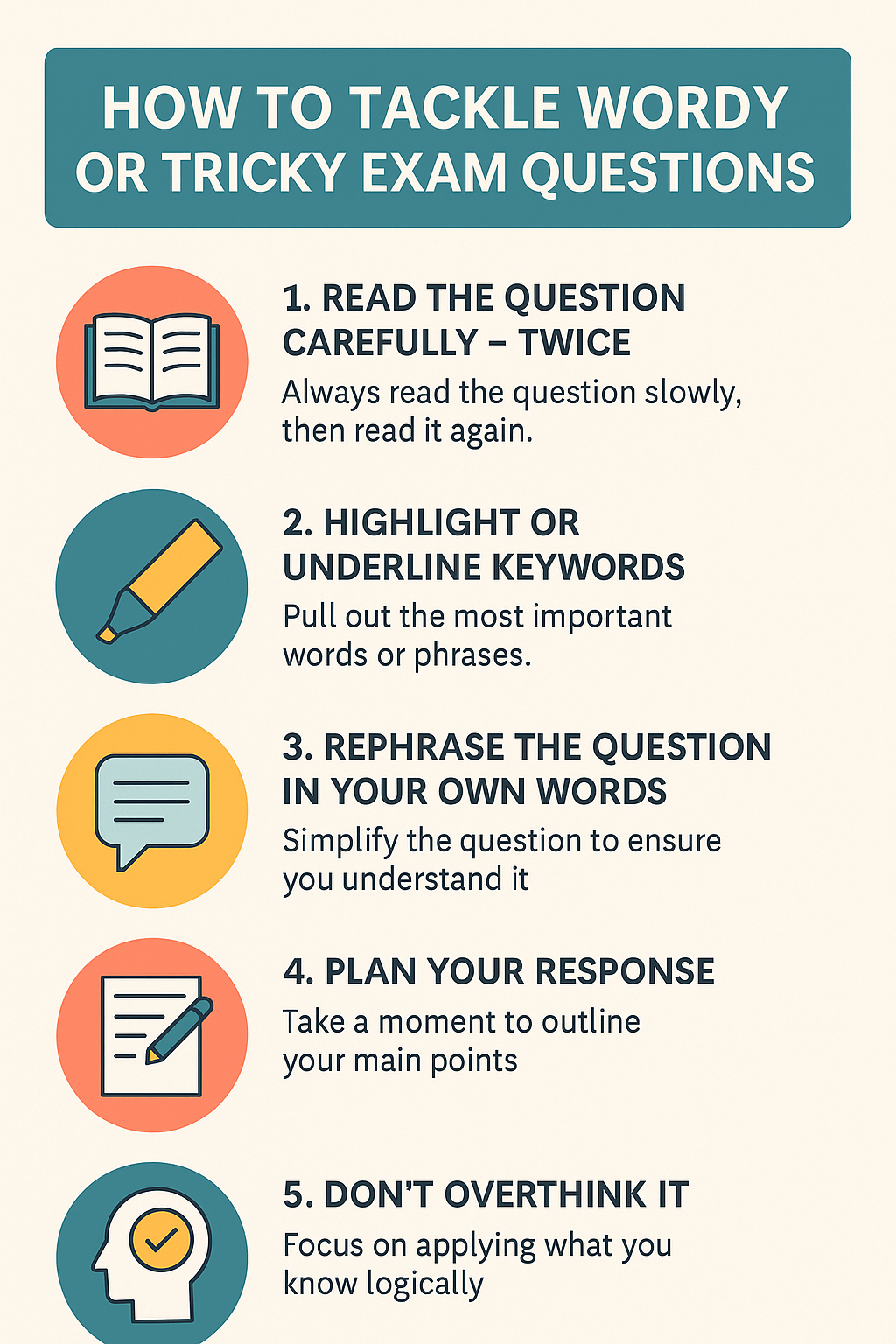

Today, I had the opportunity to observe Sophie working with a new Year 12 student in Maths Advanced. Sophie demonstrated a strong and thoughtful approach when beginning with a new student, taking the time to assess the student’s prior knowledge and identify their strengths and areas for development. This allowed her to tailor the session effectively and ensure the content was pitched at the right level. Throughout the lesson, Sophie shared a range of helpful strategies and memory aids to support the student in recalling complex formulas and methods, particularly when working with expected values and variance. Her explanations were clear and structured, helping to break down challenging concepts into manageable steps.

The student appeared engaged and supported, gaining confidence as the session progressed. Observing this lesson was highly informative, especially given the complexity of teaching Year 12 content, and highlighted the importance of clear explanations and adaptable teaching strategies. Thanks, Sophie, for a great session and for modelling such effective practice.

Sienna Apted