The Christmas holidays are always the perfect time to relax, but they are also the time where you are more prone to forgetting all of the vital information you learnt throughout the year (and especially the things you’ll need for next year)! There are so many different ways you can ensure you don’t forget anything over the break while keeping your studying fun and engaging!

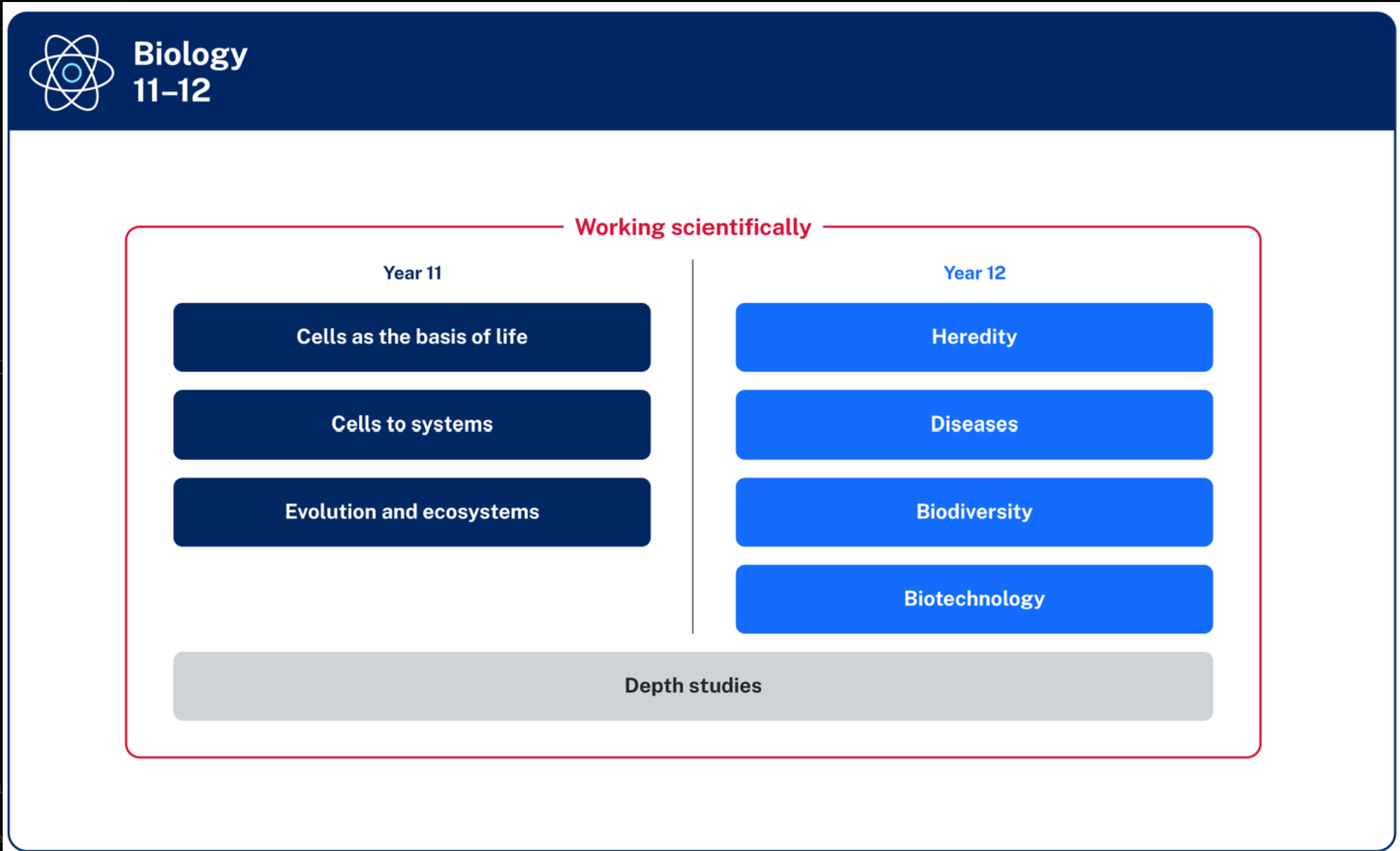

1. Set small goals over a time period

Instead of trying to revise over everything at once, focus on short, manageable sessions for each topic or subtopic. Even just 30 minutes every couple of days is more than enough to keep you on track of your work and is always good to keep your mind active!

2. Make a schedule that works for you!

Plan your study time around any family or holiday events you have coming up, so you don’t overwhelm yourself or end up feeling left out and confined to your desk. For example, a quick study session in the morning is a great way to refresh both your knowledge and your mind to take on the rest of the day!

3. Change it up!

You don’t always have to read over notes or questions when revising, you can make flash cards, mini quizzes from your tutor, active recall, or teach a friend!

4. Get other people involved!

You can invite your cousins or friends over to have a mini study session (especially if you do the same subjects or have classes together), which gives you an excuse to hang out for the rest of the day!

5. Make a reward system

If you are feeling discouraged from studying, setting yourself a reward to look forward to always gives a good boost! For example you can let yourself have a snack you wouldn’t usually have if you do a certain amount, or you can go buy something you have been wanting if you study for every second day for an entire month.

Sarah Constantinidis