Taking effective and understandable notes can make a significant difference in your understanding of the topics that you learn throughout the year when it comes time to revise for exams. Having a clear layout allows you to quickly digest the information in a way that is specific to how you learn. It is important to try different techniques so that you are able to learn which way works best for you.

1- Using colours

Having bright colours throughout your notes helps important titles and specific terms to stand out, helping you to see what you need to easily. For example, having specific colours for titles, definitions, statistics and info that you forget makes your note taking more structured. Colours also makes your notes nicer to look at (not that it is all about aesthetics), which encourages you to look over the information with more care and interest.

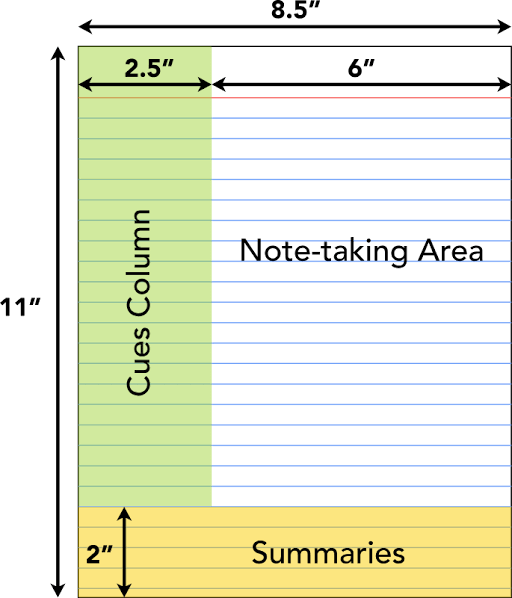

2- Cornell method

The Cornell note taking method divides your page into three sections:

– Notes – main content from class, this should take up the majority of the page

– Key ideas- this should contain any definitions, simple but important content or any questions you have. This section should be on the left hand side in a large margin.

– Summary- contain the main takeaways from that lesson in 1-2 sentences at the bottom of the page

Doing this method each afternoon after a lesson ensures you are revising the content after first learning, which is the first step towards memorisation.

3- The Feynman Technique

This is a technique that makes sure that you fully understand a topic and can apply this when it comes to exams. It works through these steps:

1. Write the concept at the top of the page

2. Explain it as if teaching a younger student

3. Identify gaps or confusing parts

4. Simplify it even further

By doing this, it easily identifies any gaps in knowledge and grasp the most important parts of the content.

Maddie Manins